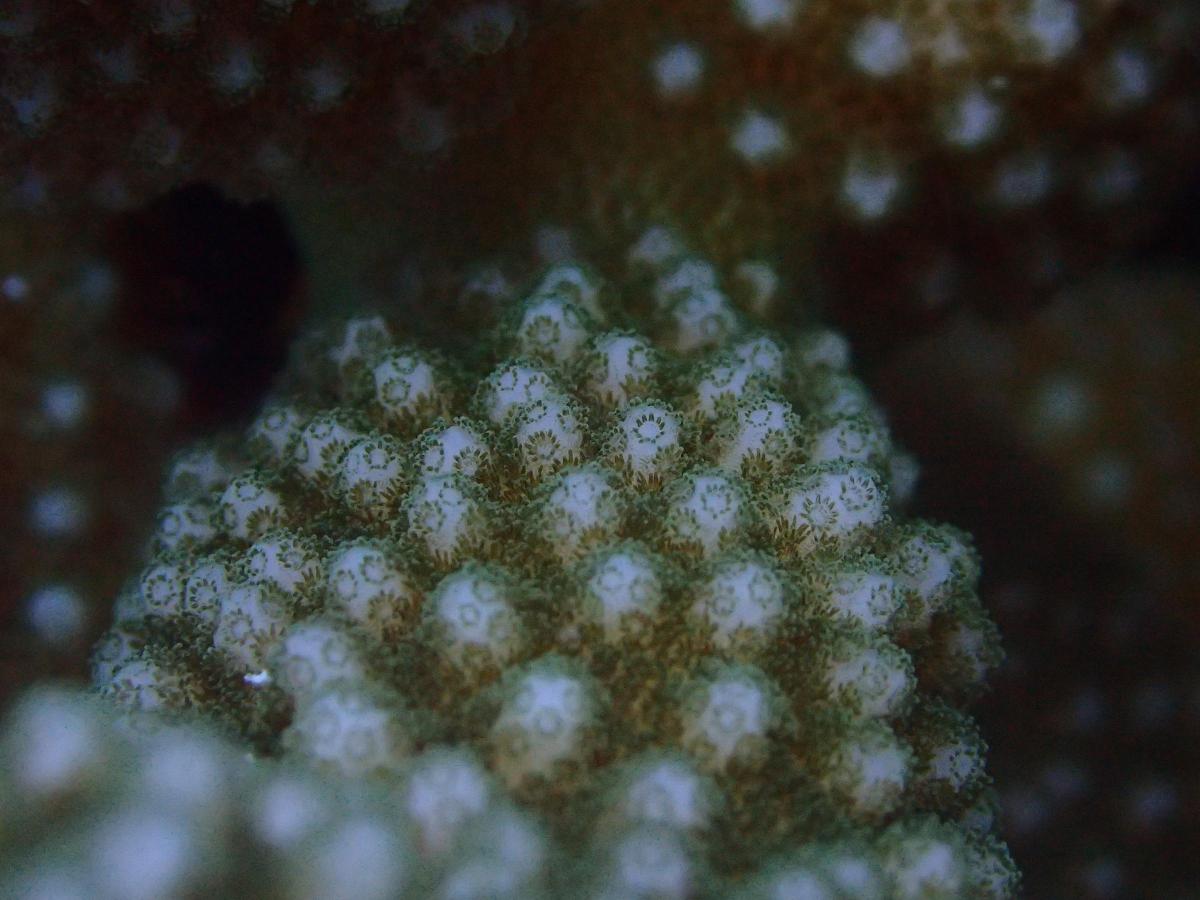

New research has revealed that tropical corals living in more productive waters take advantage of the increased food availability and that these feeding habits can be predicted from satellites orbiting our planet.

New work, which involves Bangor University, shows that corals living in waters more naturally rich in phytoplankton rely less on gaining energy from photosynthesis via their symbiotic algae and instead gain more of their energy from predating on plankton and other microorganisms.

This could mean that those reef areas richer in phytoplankton could be more resilient to disturbance events like coral bleaching, as the corals have a more abundant alternative food source.

The researchers linked the feeding habits of reef corals in the central Pacific to gradients in phytoplankton – which they measured using a satellite that tracks ocean colour. They then tested how well their model worked by taking previously published data on the feeding habits of corals across numerous oceans and showing they could accurately predict them using their satellite-driven model.

Dr Gareth Williams, Reader (Associate Professor) in Marine Biology at Bangor University’s School of Ocean Sciences who worked on the research said: “We wanted to develop a method that would allow people to estimate coral feeding habits for their reef system over broad areas without having to collect coral samples and measure phytoplankton levels themselves, so we turned to satellite technology to help us. We realised we could predict coral feeding habits accurately across numerous scales using satellite-derived estimates of primary production. We can effectively predict coral feeding habits from space.”

How much and what corals eat has been a critical knowledge gap in coral biology. The information is essential for understanding how corals are likely to persist in a warming ocean.

“Feeding can also increase the reproductive capacity of corals, which is key to repopulating reefs that have suffered high levels of coal mortality,” said Michael Fox, the graduate student from Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California San Diego, who lead the research published in Current Biology on October 18.

“What we now have is a map of potentially more resilient coral reefs. If these corals are relying more on planktonic food, perhaps they can recover from coral bleaching events faster,” he added.

“Our study is the first to take our understanding of coral feeding outside of the lab and show that global patterns of food availability likely influence the health and resilience of coral populations around the world,” said Jen Smith, Professor of marine biology at Scripps and co-author of the study.

“It is exciting to know that corals have a lot more food flexibility than we previously thought and this flexibility could help them ride out the climate change storm that is seemingly inevitable.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here